special thanks to José Castillo Lema for helping me to improve these scripts

Way back in October of 2021, I wrote a post about Setting Up a Development Environment for the Cluster API Kubemark Provider. In that piece I explained how I’m configuring Kind with Cluster API and the Kubemark provider to create “hollow” Kubernetes clusters. In the time since then, I’ve converted those instructions into a set of Ansible playbooks and helper scripts which make the automation of this process very easy. So, without further ado, let’s look at how to deploy a virtual server for running hollow Kubernetes scale tests.

Versions

Before we get rolling though, these are the versions I am using at the time of writing. I cannot guarantee that these will work in the future, but for as long as I continue to maintain these repositories they should be updated over time. Reader be aware.

- Kubernetes 1.25.3

- Cluster API 1.3.1

- Cluster API Kubemark Provider 0.5.0

- Ubuntu 22.04 Server

Process

I’m going to walk through this from the ground up. I will start by creating a virtual machine, using Ansible to update it and build the Kubernetes bits, and finally how to work my helper scripts to create clusters.

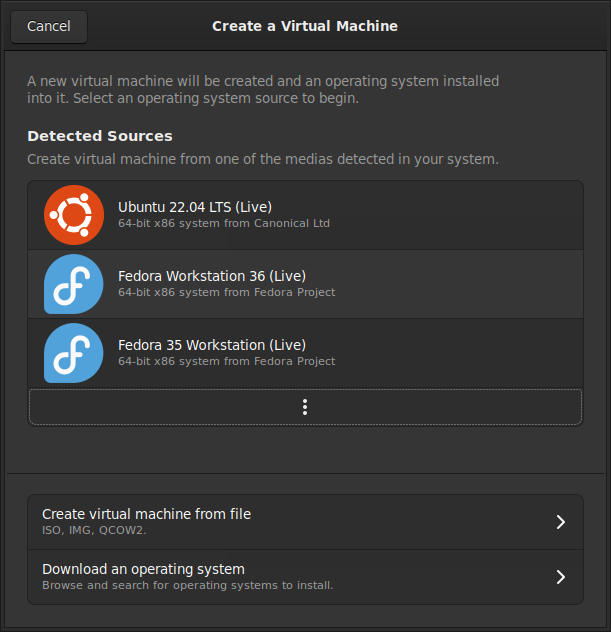

Creating a Virtual Machine

I’m using Fedora as my host operating system with the default Gnome desktop environment installed. Gnome comes with Boxes as the main graphical application for managing virtual machines. Although my host is Fedora, I like to use Ubuntu for the virtual machine because the Docker integration is a little easier for me. Kind does work with Podman but I have had issues getting the Cluster API Docker provider to work with it. An improvement I would like to make to this process is to automate the virtual machine creation process by using a script that talks directly to the host hypervisor, or perhaps using a cloud image.

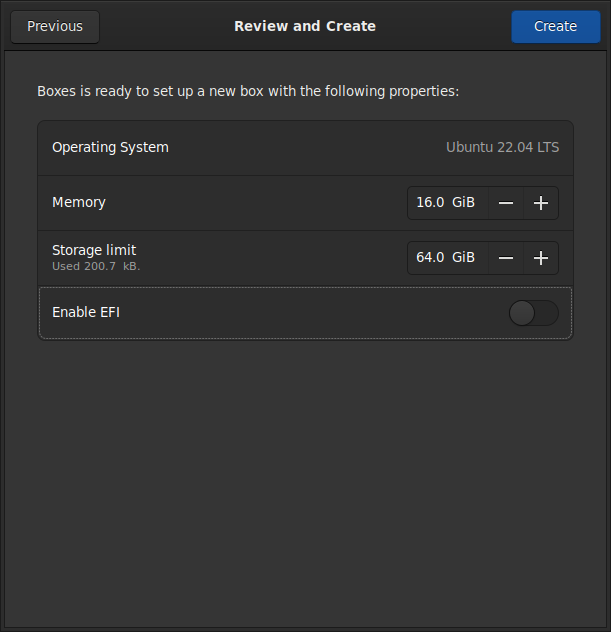

I usually create a virtual machine with 16 GB of RAM and 64 GB of hard drive space, this is enough for me to test small clusters with up to a few dozen nodes.

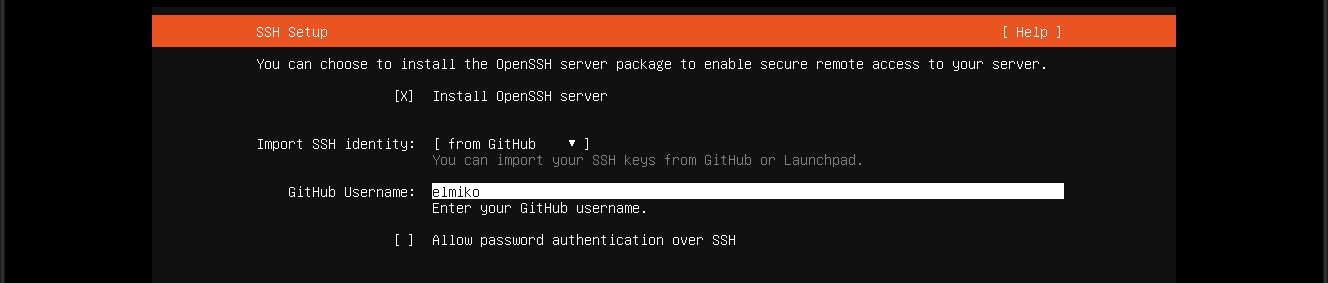

One thing I find really convenient about the Ubuntu installer is the ability to pull my SSH keys from GitHub.

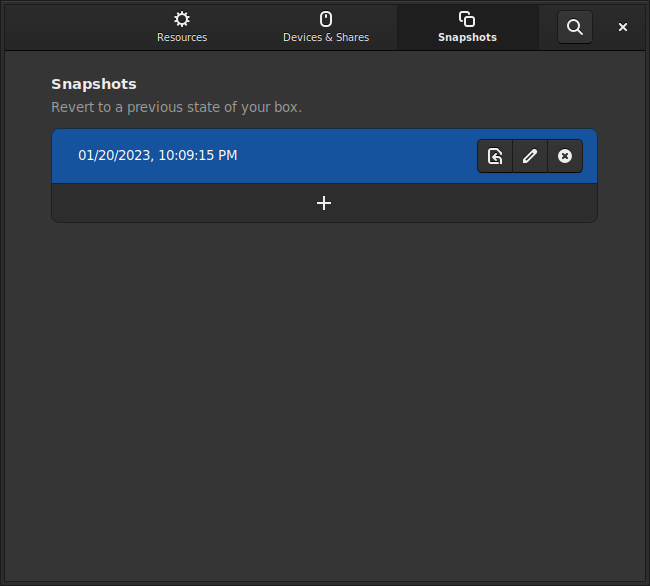

At this point I like to stop the virtual machine and make a snapshot. This allows me to quickly reset the instance back to a semi-pristine state if I feel like installing different versions of the tooling, or just want a blank slate.

Installing the Tooling

Once the virtual machine is created and rebooted, and I ensure I can login with

SSH, I clone my Cluster API Kubemark Ansible repository

to my Fedora host. This repository contains a couple playbooks; one for installing

the toolchain, and another for building the Cluster API binaries. The first thing

I do is copy the inventory directory to inventory.local and then edit the hosts

file to look like this:

all:

hosts:

192.168.122.165

vars:

devel_user: mike

cluster_api_repo: https://github.com/kubernetes-sigs/cluster-api.git

cluster_api_version: v1.3.1

provider_kubemark_repo: https://github.com/kubernetes-sigs/cluster-api-provider-kubemark.git

provider_kubemark_version: v0.5.0

This hosts file shows that my virtual machine is at 192.168.122.165, I will login

as mike, and the playbooks will install Cluster API version v1.3.1 and Kubemark

provider version v0.5.0.

After updating the inventory, I run the command to execute the setup playbook. Keep

in mind that the -K command line flag will ask for a password to become root. The

command looks like this:

$ ansible-playbook -K -i inventory.local setup_devel_environment.yaml

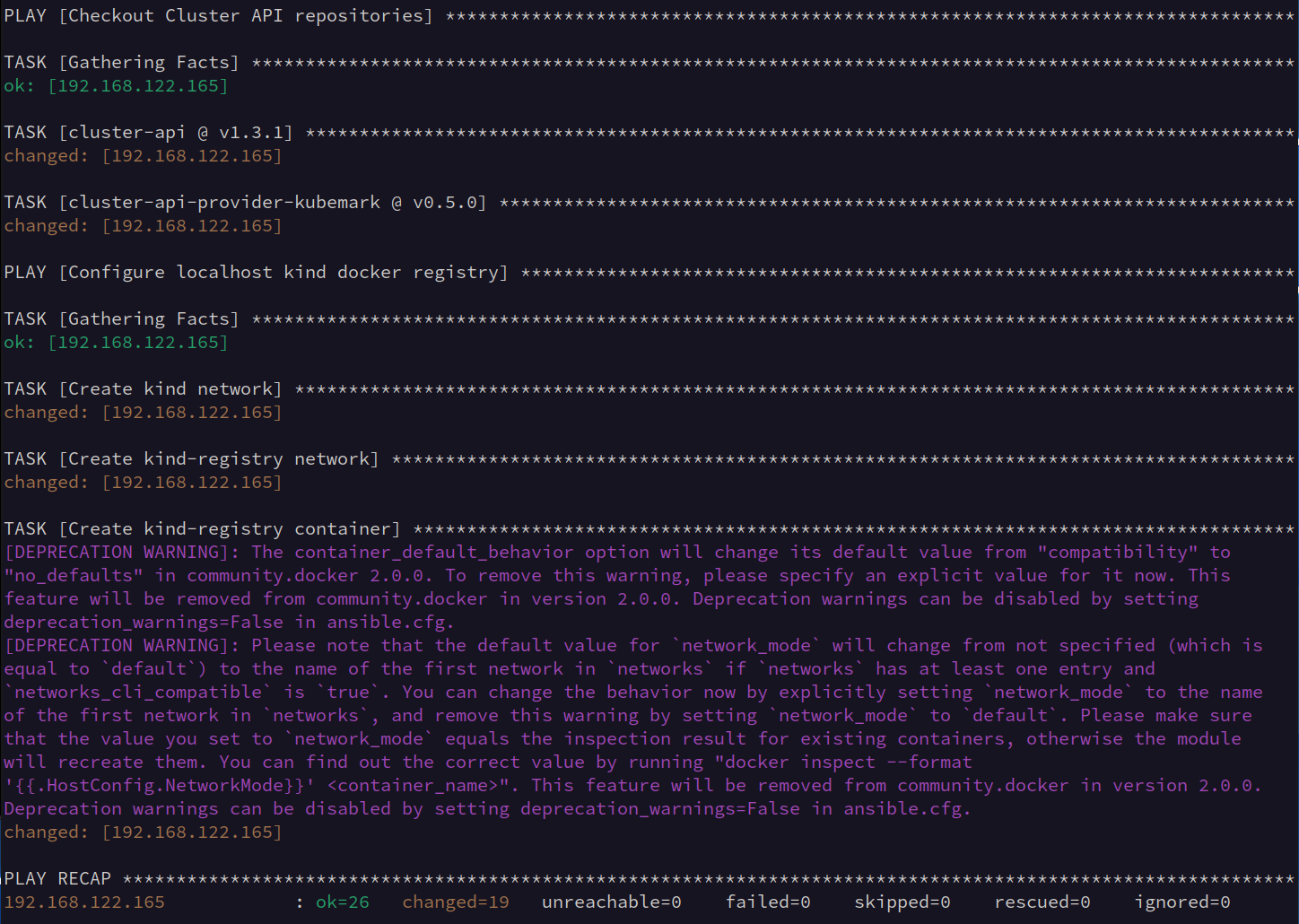

This will run for 10-15 minutes depending on connection speeds and local variables, but when it finishes it should look like this (yes, I need to investigate that deprecation warning):

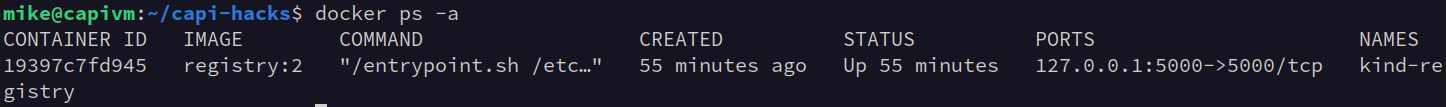

Something to note about this step of the process is that a container will be started

on the virtual machine to host a Docker registry. This container is used by Kind

so that local images can be quickly pushed into the running Kubernetes clusters.

To access it you need to tag container images as belonging to localhost:5000/.

Building Cluster API

Now that the toolchain is setup to build Go code and container images, I want to install the Cluster API project, Cluster API Kubemark provider, and then build everything. To start the process I use this Ansible command, note that this does not need root access:

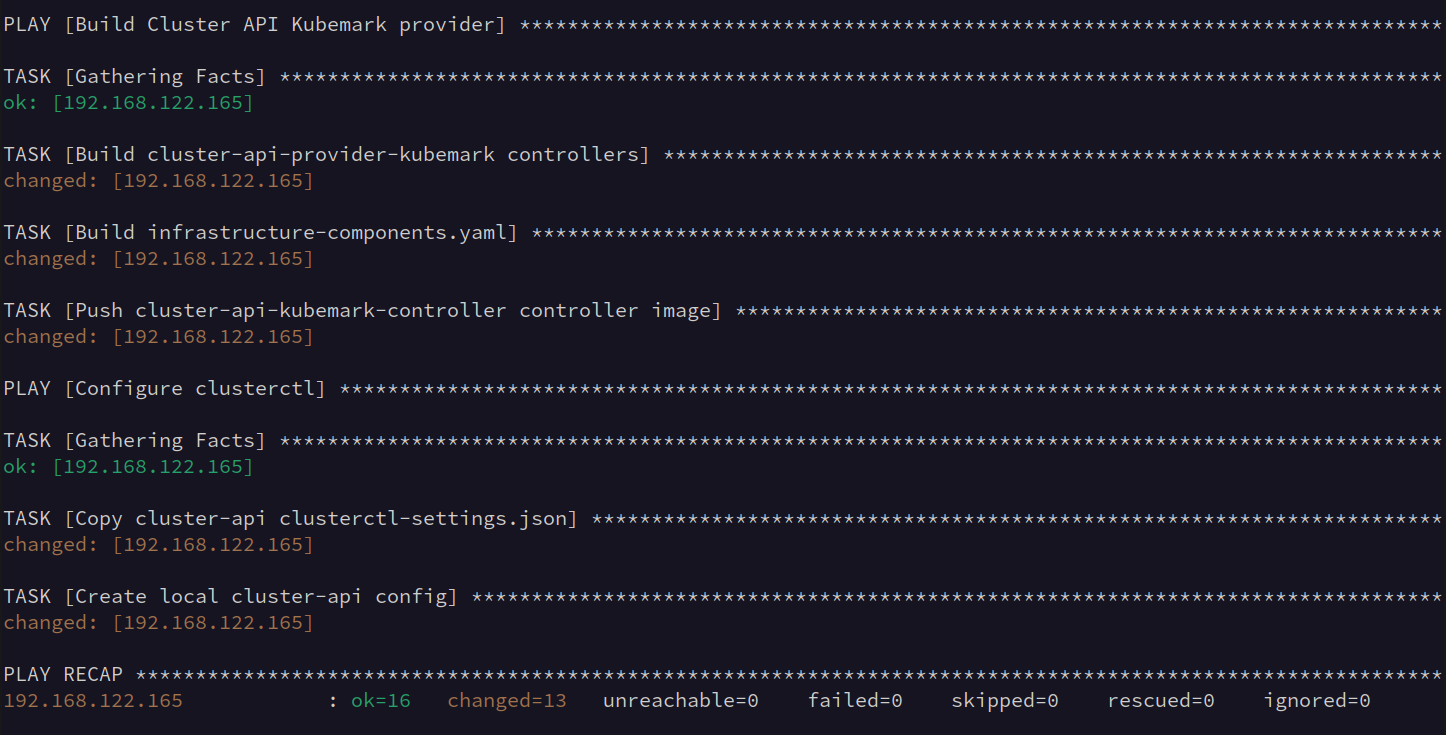

$ ansible-playbook -i inventory.local build_clusterctl_and_images.yaml

Like the previous playbook, this could also take 10-15 minutes depending on resources. When finished it should look something like this:

Preparing for Launch

The last step in my process is to install my CAPI Hacks on the virtual machine. These are a set of convenience scripts and Kubernetes manifests that I use regularly to make the process of starting new clusters easier. Let’s look at the files I use most frequently.

01-kind-mgmt-config.yaml

This is the configuration file for the Kind management cluster, it sets up a couple things including the Kubernetes version, local Docker socket location, and patch for the local registry. Usually the only reason to change this file is when updating the Kubernetes version.

kind: Cluster

apiVersion: kind.x-k8s.io/v1alpha4

name: mgmt

networking:

apiServerAddress: "127.0.0.1"

nodes:

- role: control-plane

image: docker.io/kindest/node:v1.25.3

extraMounts:

- hostPath: /var/run/docker.sock

containerPath: /var/run/docker.sock

containerdConfigPatches:

- |-

[plugins."io.containerd.grpc.v1.cri".registry.mirrors."localhost:5000"]

endpoint = ["http://kind-registry:5000"]

01-start-mgmt-cluster.sh

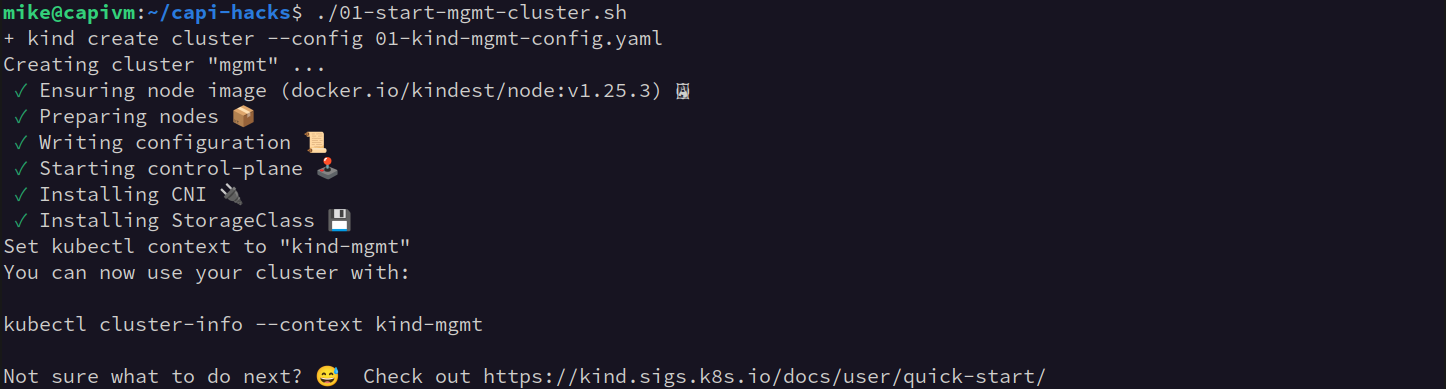

A wrapper to start the Kind cluster used by Cluster API as the management cluster.

It will be named mgmt in Kind. Running this command should look like:

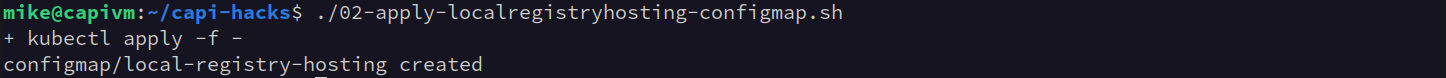

02-apply-localregistryhosting-configmap.sh

Add the local registry to the management cluster. This could probably be rolled into the previous script, but just in case you don’t want the local registry it is separate. Running this command is relatively uninteresting, but should look like this:

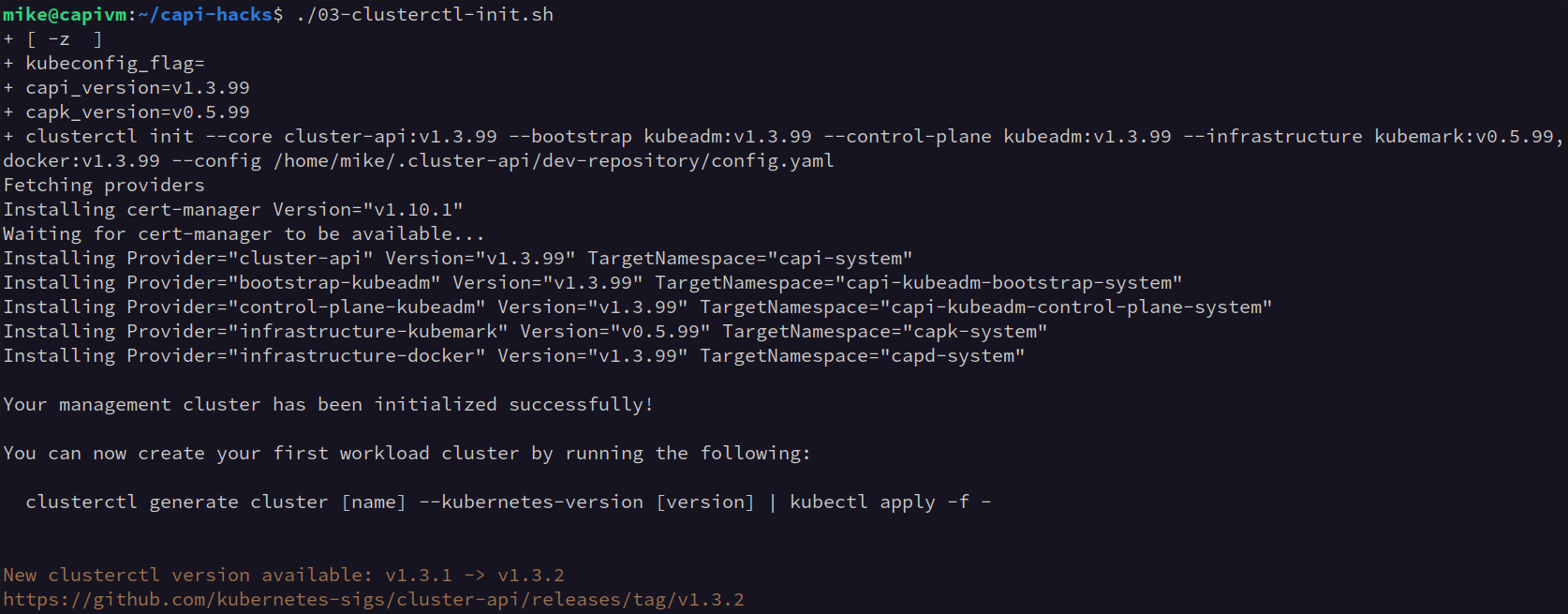

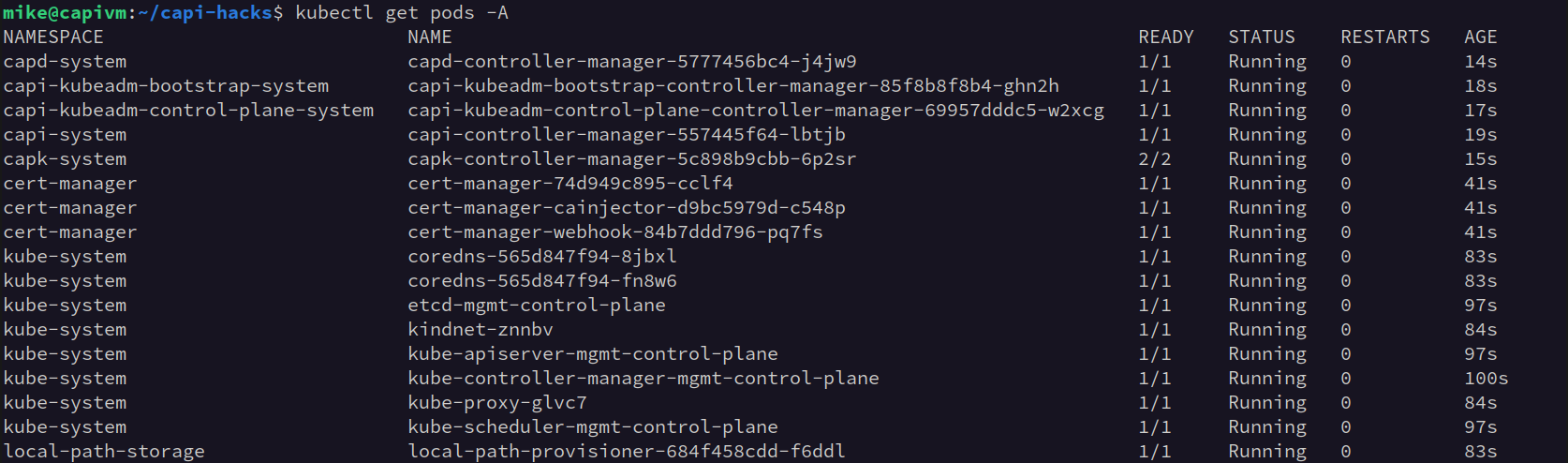

03-clusterctl-init.sh

Install Cluster API into the management cluster using the clusterctl command line

tool. This file also contains the version information for the local Cluster API and

Kubemark provider information. If it runs successfully it should look similar to

this:

I usually confirm that things are working by checking all the pods on the management cluster.

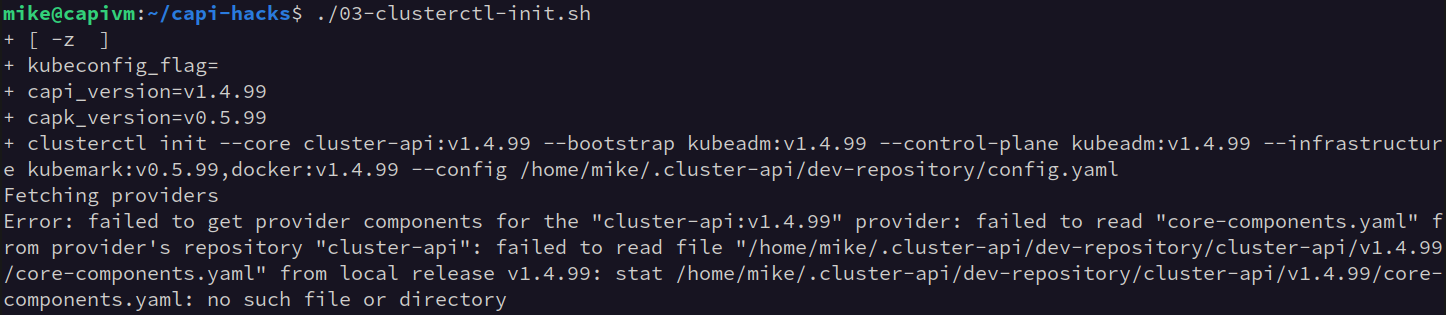

If things don’t go well, you might see an error like this:

This error shows us that we have a version mismatch between the expected and the found

versions for Cluster API. In cases like this either the version should be changed

in the script, or the configuration in the $HOME/.cluster-api directory should

be checked.

Launching Kubemark Clusters

Finally, the moment has arrived. We are ready to start deploying clusters. The

kubemark directory of the CAPI Hacks contains some pre-formatted

manifests for deploying clusters. I start by creating the objects in the

kubemark-workload-control-plane.yaml manifest file, this will create a new cluster

with a single Docker Machine to host the control plane. I am using a Docker Machine

here so that the control plane pods will actually run. After running

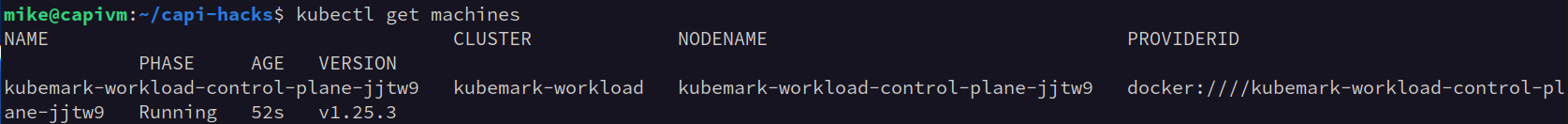

kubectl create -f kubemark-workload-control-plane.yaml, I watch the Machine objects

until I see the control plane is Running.

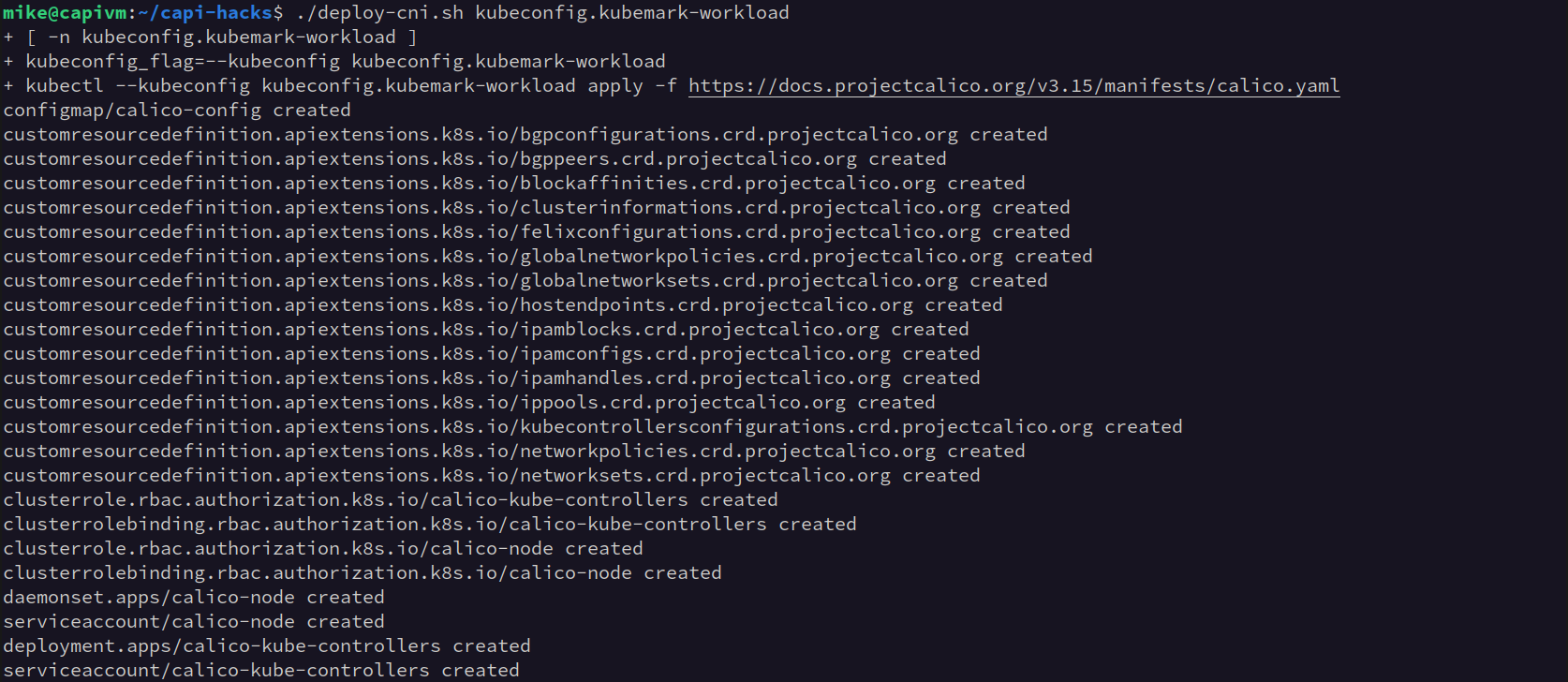

Next I apply a Container Network Interface (CNI) provider to the new workload cluster

to ensure that the nodes of the cluster can become fully ready. I use the deploy-cni.sh

script to add Calico as the CNI provider (there is also a script to deploy OVN Kubernetes).

I also use the get-kubeconfig.sh script to make managing the kubeconfig files a little

easier. When successful it looks something like this:

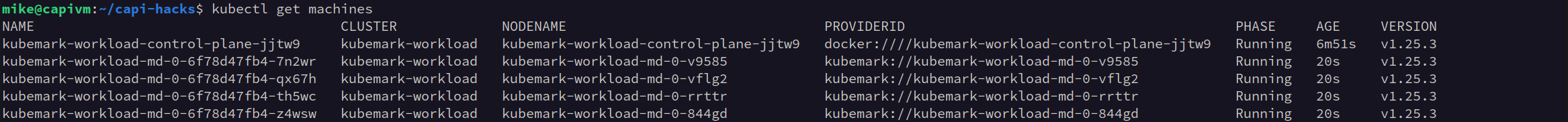

Lastly, I create the workload cluster compute nodes by running kubectl create -f kubemark-workload-md0.yaml.

This manifest contains the Cluster API objects for the MachineDeployment and related

infrastructure resources to add Kubemark Machines to our workload cluster.

Kubemark is so fast to load that within a 5-10 seconds I have all the new machines

in a running state:

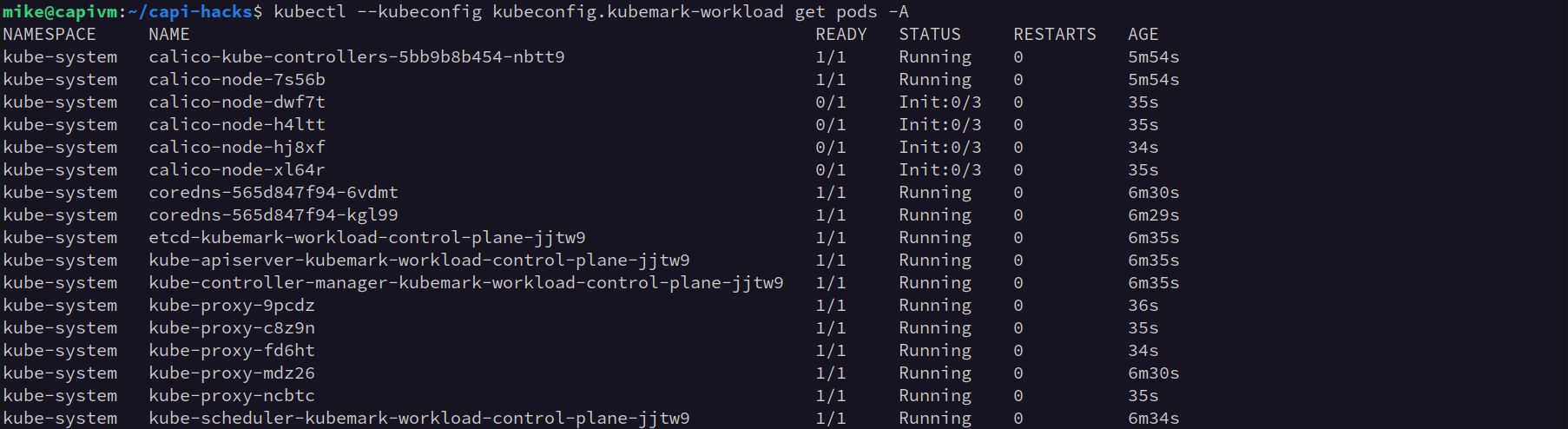

Inspecting the pods on the workload cluster you might note that the Calico containers

assigned to Kubemark nodes are stuck at the Init:0/3 status. I’m not quite sure

why this happens but I suspect it is an artifact of Kubemark, I’d like to investigate

further but for the time being it does not seem to cause problems with testing.

To the Moon!

The workflow is now nearly completely automated, or at least reduced to a much simpler series of commands. I have also found some allies along the way as people have shared suggestions, bug fixes, and improvements with me through my Cluster API Kubemark Ansible playbook and CAPI Hacks repositories.

There are more scripts and helpers inside the CAPI Hacks, after setting up clusters I tend to use the Cluster Autoscaler scripts to test the scaling mechanisms of that code. I am also learning about others using a similar workflow to test the inner working of Cluster API as well.

If you’ve made it this far, thank you, I hope you’ve learned a little more about how

to setup virtualized testing environments for Kubernetes, and maybe even tried it out

for yourself. If you have ideas or suggestions, or just want to chat about how to

get Cluster API and Kubemark working better, open an issue on one of those repositories

or come find me on the Kubernetes Slack instance as @elmiko, and until next time happy hacking =)